Bert Stern Interview

Why then return from the service and begin a career in still over motion picture photography?

I didn’t have any interest in motion picture at the time. I was trained as an art director and I got intrigued with doing photography when I was an art director for a little fashion magazine, and began to just carry a camera around, everywhere. I even carried my little Contacts all the way to Japan, throughout my army times. And when I came out I thought of becoming an art director again, or photographer. And this art director that I worked for, before I went into the army, had become the head art director of a small agency, which had an advertising campaign called Smirnoff Vodka. And they wanted me to do something a little different, so I got to do tests and when the campaign got approved it turned out that I got a chance to shoot the campaign, which led me into photography as a profession. I never thought of doing it professionally. I always wanted it as a hobby. It was something personal and it gave me an identity - well I have a camera in my hand to record what ever was around me, if I so wished. I think the movie is very much that way. It’s like moving still pictures with music. Music’s built in, so we didn’t have to orchestrate. It’s an unusual film because it’s a lot like still photography.

I understand that you weren’t particularly a jazz fan, which is in part, the reason George Avakian was brought in to support you prior to filming the festival. However, during the festival in 1958 there were performers such as Monk, Mulligan and Chico Hamilton that exemplified “newer” jazz, as well as those such as Louis Armstrong, Anita O’Day and Dinah Washington who were part of an “older” jazz set. Do you remember there being a difference and did it have any effect on how you shot the film?

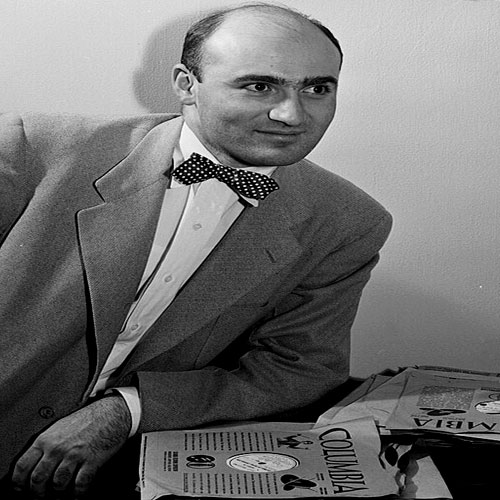

It was never a jazz film… my impression of a jazz film was, as I said, something downstairs in a dark room. As I got into developing the movie and going to see Chico Hamilton one night, I got intrigued with the sounds and that’s why I used him in the film. I had seen him perform and I thought he’d be wonderful. Almost like a leading man in the movie. George Avakian was an authority on jazz I guess, or on music, and when I decided to do the movie I went to Columbia Records, which he was the head of, to ask them if they would record all of the sound for the festival. Where usually each company recorded their own artist, my idea was to have Columbia record the whole thing and give snippets or pieces to individual companies. George was the guy I wanted to see and he got intrigued with the fact that I wanted to do this. So he was very important in the making of the movie because he knew which songs we could clear and those are the ones we decided to record. He was in the pit, you might say, and when an artist came on stage, we didn’t exactly know what they were going to play. So he would give us a sign, “let’s do this one,” and we would turn the cameras on.

Photo By William P. Gottlieb

It was said, “The welter of microphones, cables, tracking facilities for motion-picture cameras and dollies around the front of the stage, plus platforms with cameramen affixed on top of either end of the stage, gave teh festival the look of the stage set for Ben Hur.” How would you describe what you saw?

Well I don’t think it’s quite Ben Hur. There weren’t dollies. It was fairly simple. I think it added an excitement. We tried to stay back, not get in the way of the people performing and used long lenses and things like that. But there is something improvisational and real about the performances. So, getting it on film with sound - at that time - was very exciting, because that’s before videotape and the whole synching process was very complex. We had five cameras rolling at the same time and to synch them all up to the picture was complicated. It took a lot of time in the editing to find the synch to all the different cameras.

In order to finish the film, you needed to shoot additional footage - some of which was shot on Long Island, sometime after the festival. Was it something you saw during the festival, but without a camera - something worth re-creating - that led you to shoot even more footage?

What we needed was cutaways from the festival. We mainly had footage of performances and people in the audience and we needed a relief, like a break. So we devised shooting things that we didn’t shoot that went on around Newport - like parties and people dancing on roofs. We found a similar place on Long Island, I think it was Bayville, and we set that up to fill out the cutaways, you might say.

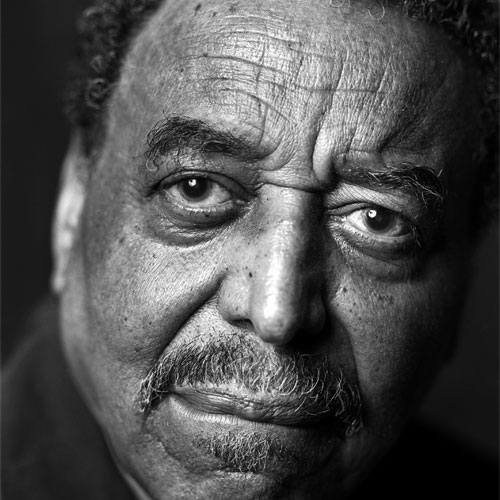

Photo By Todd Boebel

You had the unique advantage of using telescopic lenses yet there were many that said what you attempting couldn’t be done. Why? How close were you actually able to get to performers?

I adapted some of the long lenses that I used in my still photography. I had a 180-degree Sonar lens, which I used for a lot of still pictures. So I adapted that to the Arriflex which gave a wonderful look… a kind of living quality to the footage.

Looking back to those who took part in producing the picture, people like the Avakian brothers, the additional cameras, production management - guys like Harvey Kahn and Allan Green - who was closest to you and what you were doing with this film? Who did you bounce off of?

Well, Aram was probably the most experienced filmaker on the set. His brother didn’t know much about movies, I don’t think, but knew music. So the two of them were very helpful to me. They didn’t produce the film… I produced the film, but they were essential elements to bringing it to the screen because they had experience. I just had desire.

|

|

|

The Joy Formidable |

LATEST GALLERY IMAGES

Crime Scenes

Good Neighbours |

|

|