Apartheid and Beyond…

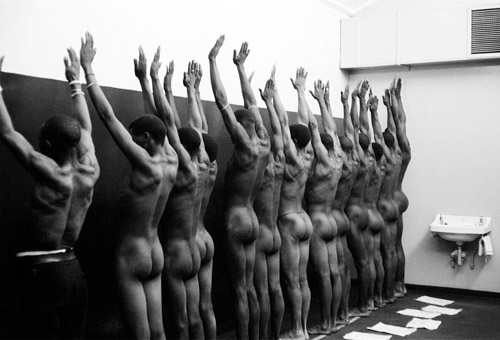

During group medical examination, the nude men are herded through a string of doctors’ offices. South Africa. 1960s. © Ernest Cole / Magnum Photos

“The Mines is a reminder of the destruction of Black lives and family structures. When looking at Cole’s photographs, I cannot help but reflect and relate - as they remind me of things that haven’t changed enough in democratic South Africa.” - Lindokuhle Sobekwa

The exhibition then shifts to “The Mines,” which captures the brutal conditions of Black miners and the exploitative labor system that underpinned South Africa’s economy. Many men were forced to leave their families and live in overcrowded, prison-like dormitories, enduring months of isolation. One of Cole’s most well-known photographs, featured in the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg, shows a group of Black men standing in line, stripped nude, as they undergo a medical check before being sent to work in the mines. The scene channels memories of slavery as well as the ongoing commodification and oppression of human bodies around the world. Hank Willis Thomas’s sculpture Raise Up, installed in 2018 at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, is inspired by Cole’s photograph of the 13 miners.

“My grandfather came to Johannesburg in the 1960s, around the same time Cole was making these works and he worked in the gold mines. He never returned home. He was one of thousands of black laborers who disappeared into the gold rush.” writes Lindokuhle Sobekwa. “One either got unlucky, injured, killed or died of illness. Or became a fugitive trying to escape the terrible working and living conditions. ‘The Mines’ is a reminder of the destruction of Black lives and family structures. When looking at Cole’s photographs, I cannot help but reflect and relate - as they remind me of things that haven’t changed enough in democratic South Africa.”

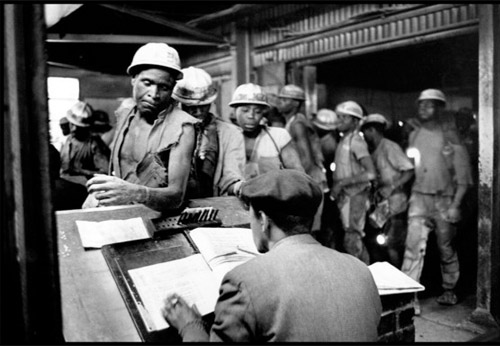

South Africa. 1960s. © Ernest Cole / Magnum Photos

According to Struan Robertson, the miners had to be checked off against their individual numbers on their bracelets when they went on shift. The same was true when they came off shift.

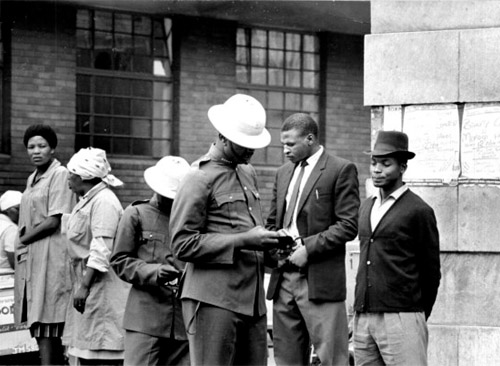

Many of the images in the book and exhibition seem as if they would’ve been impossible to capture, and indeed, Cole was risking his life. “He had a paper bag with a hole and his camera in it,” Sanders said about one of Cole’s covert photography techniques. “Ernest, as a character, was not a big man and was quite quiet in temperament, so he would just kind of blend in. People wouldn’t pay him any attention. Meanwhile, he was busy taking all the photographs that he needed. He had a super sharp mind, and the sign of a great reportage photographer is someone who sees the action taking place in front of them and then very subtly is able to get the shot without anyone noticing.” Additionally, Cole had himself reclassified from “Black” to “Colored,” which allowed for slightly less scrutiny of his movements and activities.

1960s. © Ernest Cole / Magnum Photos

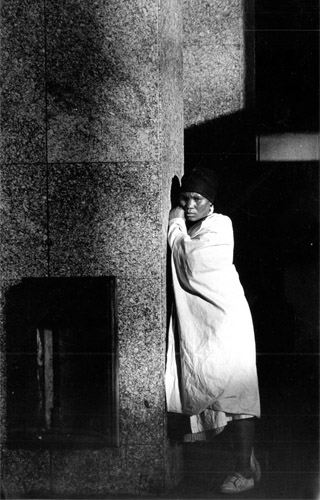

The section, “The Cheap Servant,” on the flipside of men’s work in the mines, shows some of the roles designated for Black women. One image that Sanders calls “unusual” for Cole, portrays a Black woman wrapped in a blanket leaning against a granite wall. The contrast between the woman’s fragile humanity and the hard, unyielding surface seems to be an apt metaphor for Apartheid itself. On one side, the granite of what may be a bank or office represents the unrelenting power of the white, capitalist, Apartheid regime - its institutions, its wealth, and its cold indifference to human suffering. On the other side, a woman stands cloaked in quiet resilience.

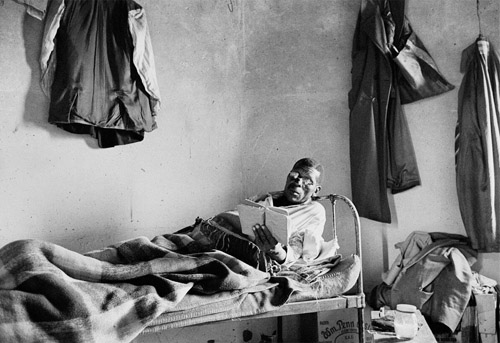

Theophilus Tschangela lies alone in his sickness and reads his prayer book. His mattress is a jute bag filled with grass. South Africa. 1960s. © Ernest Cole / Magnum Photos

Another chapter, “Banishment,” explores the forced removal of Black leaders from their communities. These activists were exiled to remote areas and stripped of their influence and support. Cole spent some time living among them, documenting their resilience in isolation. Despite their exile, many of these men remained engaged in intellectual discourse. One print depicts Leonford Ganyile, with a book in hand, reading by paraffin lamp. His engagement with the written word is a testament to the endurance of those who refused to be broken by the harsh conditions of Apartheid.

|

Midlake |

LATEST GALLERY IMAGES

Crime Scenes

Good Neighbours |

|

|