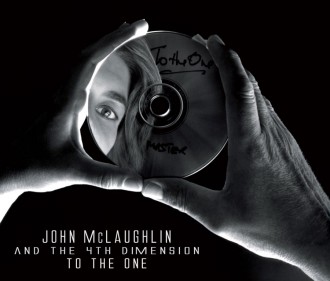

John McLaughlin & the 4th Dimension

“But by the mid ‘60s,” he continues, “the hippies were all dropping acid, and I was in there with them… experimenting with feedback and big amps. Prior to that, I was a jazz snob - but then came Revolver and Sergeant Pepper. Then Hendrix. By 1967, I was trying to experiment - trying to get distortion. By the time I arrived in New York City in January 1969 to play with Tony Williams Lifetime, I was caught between two worlds: classic jazz and this new music. I arrived at just the right moment.”

What unfolded then was an amazing path, as McLaughlin became a key presence on several of Miles Davis classic sessions (Bitches Brew, A Tribute to Jack Johnson), founded the incredibly influential Mahavishnu Orchestra, explored Indian music and spirituality with Shakti, and continually sought out bold new contexts for his expressive and inventive playing. All the while, McLaughlin continued to draw musical and spiritual sustenance from John Coltrane’s legacy - internalizing Coltrane’s expansive rhythmic approach (which eventually transcended Western ideas of beats and measures) and the organic ebb and flow that underpinned Coltrane’s marathon improvisations. He explicitly explored Coltrane’s music on 1994’s After The Rain, accompanied by the great Elvin Jones and organist Joey DeFrancesco.

“I had the opportunity to make that record with Elvin,” McLaughlin explains, “and I seized that opportunity. Elvin is a big part of my history and part of my life. But, in all honesty, it took me until now to truly synthesize these principal elements of Coltrane’s music, and how they coincided with my own spiritual endeavours. It took 45 years to find a coherent hybrid. It’s an internal thing, this synthesis, and I finally feel that I am able to express it in a musical way.”

That expression, captured so immediately on To The One, is vividly enhanced by both the skill and soulfulness of the Fourth Dimension. “I rely on the band 100 percent,” McLaughlin enthuses, “and I know that I can do that: they are all outstanding, each of them. The kind of music it is demanding, technically and musically. The melodies are not easy, and the rhythmic structures are unusual.” Yet, rather than get bogged down in the mechanics and mathematics of the songs, Husband, M’Bappe, and Mondesir tackle them heroically – not only executing the material, but finding expressive inspiration within the challenges that the songs present. “Mark Mondesir can play in any rhythmic formation or time signature and make it sound natural,” McLaughlin explains. “Gary is both a drummer and a keyboardist, and he approaches the keyboards with a kind of rhythmic insight that no one else has. Etienne, who I first heard with Joe Zawinal, is so fluid, so solid. ‘Lost and Found’ was the first time he had ever played in eleven, and he did so beautifully.”

From the rampant opener “Discovery” to the gently propulsive title track which closes the compact, forty-minute program, McLaughlin’s own playing is at its very peak: emotional and probing, exploding one moment, candid and unguardedly vulnerable the next. “For the band to play my tunes is a challenge,” McLaughlin explains, “and in return, I want them to challenge me. This is part of what jazz is – it’s very interactive. You play with the musicians. You’re not just playing the notes. We filmed ourselves recording the song ‘The Fine Line,’ while making this record, for the website or YouTube. We did two takes: one version is really good, and the other one falls apart. I want people to see both – so that everyone can see that we are human. Mistakes happen. It’s nice to witness, because it’s funny and it’s human.”

“The spiritual search is not just deep and dark,” McLaughlin continues, “it has humor too. If god exists, he’s the greatest comedian ever…” In light of the inspiration behind To The One, there is one great irony not lost on McLaughlin: “I never saw Coltrane perform in person. The one time I was in the UK and he was playing, I had a gig! I was in an R&B band and we were booked on an American air force base! He had a concert in London and I missed it…but in those days, if I had a gig, I took it. I had to eat! “Yet, I remember when I read of his passing, in 1967,” he remarks more somberly. “I was in a bus, standing up, and I read it in a newspaper, over somebody’s shoulder. I couldn’t stand up. My legs went wobbly, I had to sit down… this was how close I felt to him then. When Miles passed, that was just hard for me. I grew up with these two men in my life. They were my gurus.”

To John McLaughlin, reflecting on To The One means looking back on a life both musical and spiritual, and how the two intertwine and continue to enrich one another. “I believe we’re all here to discover our true identity and the unity that binds us together,” he concludes. “Music brings that out, because you can’t hide in music. As we grow in life, we begin to change, we hear music differently, and what we do in life directs what we do in music. How we are in life is how we are in music. If one person in the band gets it, the rest of the band can get, it, and the audience can get it. It is impossible to organize, because it doesn’t depend on you – it depends on the all, it depends on an everything greater than just what you can control.”

|

|

|

Europe |

LATEST GALLERY IMAGES

Alanis Morissette

Where Israel Goes, Misery Follows |

|

|