Merlin Of Rock: Jimmy Page

If any Zep album could be called career-defining, then it would be the stampadorning fourth, containing Tolkien-esque lyrics, enigmatic runes on the album sleeve, Plant at his most swaggering and Page’s most famous song, Stairway to Heaven. “I think every track on it has proved to be an absolute classic,” Page says. He courteously indulges me with his slightly hazy memories of the album: of recording Stairway (“In the rehearsal, Robert was very quiet while he wrote most of the lyrics; then he just let fire!”), of Rock’n’Roll being done off the cuff, of how the trance-like tumble of Four Sticks was avant-garde and how the spookily atmospheric location of Headley Grange, Hampshire, where they recorded the album, was an inspiration.

The gatefold sleeve’s iconic symbols and inside illustration based on a Tarot card of a hermit holding a beacon of light were a conscious effort by Page to create the band’s own quasi-mystical mythology. The effort worked almost too well, and the variously absurd rumours of devilry around Zep remain a source of perpetual fascination. Even in the most recent band biography, by the seasoned rock journalist Mick Wall, there are lengthy explorations of occult resonances in the album’s imagery. Is there, for example, really a two-headed beast drawn into the rocks below the hermit, seen only if held up to a mirror?

Somewhat evasively, Page explains: “The point about the music and the album covers was to be something that would be thought-provoking, hopefully on an intellectual or an emotional level. Whatever Mick Wall’s written about the hermit is probably so off. It doesn’t matter. The cover was supposed to be something that was for other people to savour rather than for me to actually spell everything out, which would make the whole thing rather disappointing on that level of your own personal adventure into the music.”

If Page is ever irked by the speculation concerning this side of the Zep he surely can’t find it surprising. During the 1970s he famously became something of a scholar of the life and work of “wickedest man in the world”, Aleister Crowley, extending to Page owning an occultist book shop and buying the Great Beast’s manor, Boleskine House, on the shores of Loch Ness (he sold it in the early 1990s). Does he still have such an interest in, shall we say, magick? “Well, I’d prefer not to talk about it, really.” It’s hard to tell if the question affronts him, but it feels as though he half-expects it.

Crowley’s credos of self-liberation, not least via sex and drugs, fitted well with Page’s rock-star existence and the level of success the band experienced. Stories of the band’s groupie-tastic, coke-fuelled, booze-binging exploits on tour have captivated the imagination of rock fans ever since. If their excess wasn’t really anything their peers weren’t doing too, then Led Zeppelin’s imperious, untouchable manner, their private jet, the accompanying chaos set them apart, evoking to this day the ultimate rock-stars-on-the-road fantasy. Anecdotes concerning Page being served on a room-service trolley to a room of nubile young women sound like any lusty young man’s dream. But Page has never and won’t substantiate — or deny, it should be said — any of the wild tales. “The tours took a lot … well, did it take a lot out of me? I don’t know whether it did. It gave as much to me as it took out,” he says. “It was like being on a permanent adrenalin drip, d’you know what I mean?” Playing live, at least, was “to be right on the edge of the moment”.

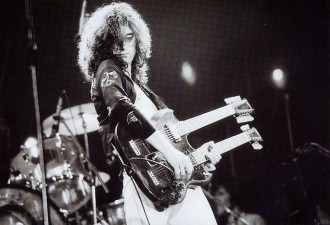

Indeed, by 1973, on stage Page was a marvel to behold, whipping himself into rock-star poses as he improvised virtuoso solos with tireless, sweat-pouring intensity, even employing a violin bow drawn over his Gibson Les Paul guitar strings to create eerie, ear-bleeding effects. His costumes became more flamboyant, embroidered with glittery moon and stars, poppies and dragons. Today, they are very much part of rock iconography — I wonder if he still has the famous suits. “Yes I do. Oh, yeah! Carefully stored. The only thing is I’ll never get in ’em again! I think the waist on them is 26in. Absolutely ridiculous!”

What does he make of the rock biographies, such as Stephen Davis’s infamously salacious Hammer of the Gods or, most recently, Wall’s “definitive” tome? “I don’t actually read them, I just hear about them from other people. I did see Wall at one of those award ceremonies and I just told him: ‘I wanted you to know I’m writing a book on Mick Wall’ ”

As we linger on this stuff, though, his sense of humour starts to desert him. The mood darkens as I get on to the subject of the bad energy and harder drugs that crept into the Zeppelin picture in the late 1970s, when Page became near-skeletal in appearance and the Zep juggernaut was shaken by a chain of tragedies, including the death of Plant’s five-year-old son Karac from a viral infection.

|

|

|

Black Stone Cherry |

LATEST GALLERY IMAGES

Where Israel Goes, Misery Follows

The Kanneh-Masons |

|

|