CHERNOBYL By Serhii Plokhy

Covid Read CHERNOBYL By Serhii Plokhy. Penguin 2018

With democracy under threat in many countries and authoritarian rule on the rise, my latest read was of prime relevance. CHERNOBYL, the book, is extraordinary in its detail of the event and exposure of the lack of openness of the Russian regime at the time (of course much worse now). It is also relevant to the current events in the Ukraine, the questionable communication of Covid by the Chinese authorities, the current USA’s presidential decrees, and the attempts at circumventing democracy right here in the UK (especially with the substantial masking of the real economic implications on leaving the EU, and the current apparent doubts over Covi-19 death and infection statistics). There are sadly many other examples causing hardship and harm to millions of people. Chernobyl ultimately led to the demise of Mikhail Gorbachev (the authur of a more capitalist, democratic and West-friendly Soviet Union) and break-up of the Soviet Union.

“The bare outline of the Chernobyl fire and the Soviet silence have been well covered…Mr. Plokhy, who directs the UKranian Research Institute at Harvard, adds much detail to the construction that caused the failure, and the false assignment of blame to operating engineers…His most telling disclosures deal with how the Soviet subterfuges played a major role in Ukraine’s decision to become an independent nation once the Soviet Union disintegrated.” - Washington Times

In this series of features, I have picked book passages that reflect today’s problems and challenges.

At around 7:00 a.m. on April 28, 1986, Cliff Robinson, a twenty-nine-year-old chemist working at the Forsmark Nuclear Power plant two hours drive from Stockholm, went to brush his teeth after breakfast. In order to get from the washroom to the locker room, he had to pass through a radiation detector, just as he had done thousands of times before. This time was different, though - the alarm went on. It made no sense, thought Robinson, as he had never entered the control area, where he might have absorbed some radiation. He went through the detector a second tiume, and again it went on…

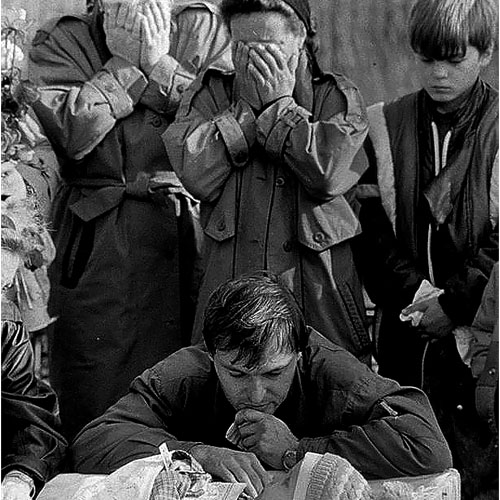

What happened in Prypiat stayed in Prypiat. That had been the rule before the accident, and it remained in effect for days afterward. Even though tens of thousands of people were evacuated from Prypiat and nearby villages, the Soviet government refused to tell its citizens and the world at large what had happened. Television, radio, and the newspapers, even local ones in Ukraine, remained silent about the accident.

The Kremlin had been quite successful in keeping previous large nuclear accidents under wraps, remaining silent about radioactive pollution and the dangers it posed to Soviet citizens and the rest of the world. That was the case with an accident that took place in 1957 in the closed city of Ozersk in the Urals, better known to the Soviet leadership under the code name Cheliabinsk-40 - the home of the first Soviet nuclear fuel plant producing weapons-grade plutonium. On September 29 of that year an underground nuclear waste tank had exploded, blasting a concrete cap weighing 160 tonnes from the tope of the steel and concrete container and releasing 20 million curies of radioactivity into the atmosphere…The Soviet leaders refused to release information about the Ozersk explosion, thereby endangering the lives of hundreds of thousands of their own citizens, who went on with their daily routines not knowing how to minimize the risk caused by the accident.

Original silence about the Chernobyl accident at home and abroad also followed the Ozersk pattern. In 1986 Mikhail Gorbachev, Nikolai Ryzhkov, and their subordinates in Moscow and Kyiv had a model they could follow not only for dealing with the nuclear disaster, but also for speaking - or rather, remaining silent - about what had happened. The tradition of complete secrecy about the nuclear programme, the regime’s unwillingness to admit disaster after having prided itself on being the first to build a nuclear power plant and successfully managing the peaceful atom (incompetence in that regard had hitherto been attributed only to the United States and the capitalist world), and, finally, concern about unleashing panic and a resulting inability to mobilize the resources needed to fight the disaster - all that came together in the deafening official silence that prevailed for the first days after the explosion.

But this time it proved more difficult to restrict the flow of information. Whereas the Ozersk accident had released 20 million curies of radiation into the atmosphere, the Chernobyl disaster released 50 million curies. Besides, Chernobyl was not in the Urals - the middle of the Soviet Empire - but closer to its western edge, and the winds spread radiation, and thus awareness of the accident, to the countries of Northern and Central Europe.

…Swedish nuclear specialists soon figured out that the radiation they detected had been carried by winds blowing from the other side of the Baltic Sea. Swedish diplomats contacted three Soviet agencies whose activities involved nuclear power and asked for possible explanations. They got none….

The Soviet media finally broke its silence on the Chernobyl accident at 9:00 p.m. on Monday, April 28, almost three days after the accident and more than twelve hours after high radioactivity had been detected in Sweden. In a dull voice, an announcer on the evening news programme Vremia (Time) read a brief bulletin from the Soviet news agency TASS. Its text was as follows: “An accident has taken place at the Chernobyl atomic electricity station. One of the atomic reactors has been damaged. Measures are being taken to eliminate the consequences of the accident. Assistance is being given to the victims. A government commission has been struck to investigate what happened.” That was it…

Page: 1 2

|

|

|

Wallis Bird |

LATEST GALLERY IMAGES

Alanis Morissette

Where Israel Goes, Misery Follows |

|

|