Beinhorn on Pre-Production

Honing Musicianship (Implementation)

The analysis, discovery and revision phases of pre-production involve examining songs under a microscope. By comparison, the implementation/rehearsal phase involves examining performance aspects of the songs from more of an overview.

After a few days of doing revisions, the focus gradually shifts more to rehearsing. Depending on the style of music, I start pre-production with a full band. Sometimes, I start only with vocals and one instrument for accompaniment in order to focus exclusively on song structure (and gradually add the rest of the instrumentation to see how everything interacts). No matter what instrument configuration we begin with, I focus on the rhythm section as early in the process as possible. I feel that quite often, bass and drums are treated as afterthoughts instead of essential parts of a band and I often work with them separate from the other instruments.

Why focus on bass and drums?

1) Although often ignored, they are foundational, supportive and propel the other instruments; 2) they potentially provide great rhythmic and melodic counterpoint for the vocal; and 3) I feel they always sound better when played with feel and aggression, instead of being polite and stiff, but spot-on with a click.

People often make jokes about bassists and drummers, but a great rhythm section makes a song come alive. On the other hand, a great song can fall apart when the rhythm section isn’t doing their job. A cursory listen to any Beatles record will thoroughly prove this point.

As I mentioned earlier, when a band comes into pre-production well rehearsed, we are able to implement changes much faster because they are prepared. This also means that we can focus heavily on nuances in their performances, relationships between the instruments, how aggressively the songs are attacked, etc. The musicians are better able to play with more intensity and get the maximum impact from their material.

Sometimes, however, a band is relatively unrehearsed prior to pre-production. When this happens, pre-production becomes a chaotic overlapping of arranging, revising and rehearsing. Suffice it to say, this is never ideal. Rehearsing consistently makes a performer better at what they do and a better performer guarantees a better performance. Experience has shown me that people always prefer listening to a great performance than a mediocre performance that has been heavily edited.

We who make recordings are quick to believe that average listeners can’t hear any difference; but, believe me - they can tell.

Building Morale

There is also an interpersonal aspect to pre-production (and record making in general). Since creative work often boils down to people working together in a room, it involves relationships. Because I forensically analyze an artist’s creative work (with the consideration that I may have to rip some of it to shreds), the dynamic of my relationship with the artist can be affected.

Generally speaking, people doing creative work in any environment are happy and productive. Conversely, an environment inhabited by a group of artists jointly working on the foundation of a creative project is fragile and potentially volatile. Along with each individual’s ideas, his ego is also on the table. Depending on a variety of factors, anything can cause the mood in the room to go from cool to boiling hot in a split second. Perhaps one band member doesn’t like a particular song that another one wrote. One band member might become offended by another band member’s flippant comment, or someone had a bad morning prior to beginning work.

In this case, how do I - as the designated driver of this project - constructively handle ongoing interpersonal dynamics? How do I critique an artist without demolishing his confidence? How do I keep everyone in the room happy, working well together, with the same general goal in mind while navigating around any stray agendas that might be detrimental to the project?

Apart from helping hone the artist’s material, my job is to maintain stability. In this aspect, I have to be an office manager, a psychologist, a parent and a traffic cop. To handle those roles well, I come into pre-production prepared. This starts by knowing all the music and having a comprehensive plan to make it better. And, to reinforce that, I come in calm and relaxed. In a work situation involving multiple individuals, one person’s mood and state of mind can affect everyone else’s mood (as well as their ability to concentrate); hence, maintaining my calm helps everyone keep theirs.

For this reason, I always make sure to leave my personal issues outside the rehearsal studio door. I also try to meditate prior to starting work. If there is a disagreement, my responsibility is to maintain a constant overview of the situation. Remaining calm facilitates a better sense of that overview. I am also conscious of not getting sucked into anyone else’s personal drama. Drama is seductive, especially in a creative environment. However, it serves absolutely no purpose when it manifests in a group of people trying to work. Looking past the cause of drama enables one to maintain clarity.

When I see what is at the root of a specific problem, I parse out all the individual elements that make up the problem and present them to the artist as concrete facts with concrete solutions. I find that people often get frustrated because they are trying to address a multitude of stressful things at once, instead of separating them and dealing with them one at a time. Bringing clarity to a situation makes it easier to defuse.

Providing critique is an essential aspect of my role. When I critique or share ideas with an artist, I keep in mind that the artist may be extremely close and attached to his work; hence, I do it with care. Often, the way information is presented is as important as the information itself.

The most important thing of all is keeping the creative atmosphere positive and upbeat. The best way to do this is to make sure there is a constant sense of progress. Few experiences are better than hearing a familiar piece of music transform, reveal all its potential and recognizing your own contribution to this metamorphosis.

Some Final Thoughts for the Artist

Producing an artist implies that there is a collaboration between the producer and the artist. Even if a producer has written songs for an artist’s project, the artist’s name is still the first thing people identify with that project.

The relationship is symbiotic, not hegemonic. An artist may consistently defer to a producer by choice; however, this is not appropriate if the artist disagrees with the producer or feels compelled to speak his mind.

What you create is based largely on your own creative instincts. Therefore, as an artist, while it is imperative to accept input, it is equally imperative to trust your instincts and to assert yourself when the situation calls for it.

You may find yourself working with a producer, perhaps someone with a lot of credits and success behind him. Things may be progressing smoothly when, suddenly, he drops an idea on you that you don’t like. In fact, it is an awful idea, one that has (at least, in your mind) absolutely nothing to do with the kind of record you want to make.

What do you do?

Obviously, being open-minded and tactful is a lot more valuable to you than being quick to reject the idea without giving it a chance. Since it might help you to understand why he made the suggestion, you can ask him to explain it. Perhaps, after he has explained his idea, it still doesn’t make sense. In this case, the next step might be to tell him that although you are still unclear about what he’s going for, you are open to trying his idea, but with conditions. The first condition might be that you’ll try his idea, but you might also want to try your own idea in place of his and compare the two. The second condition might be that if his idea doesn’t work - even after living with it for a time - the song will be restored to the way it was.

This way, a potentially difficult situation becomes a reasonable compromise; one free of conflict where everyone stands to win.

One of my favorite quotes is from novelist William Faulkner and it reads, “In writing, you must kill all your darlings.” The killing of your darlings, which in this case might be losing a song part that you love but simply doesn’t work, is one of the most difficult - and transformational - things that you can do as an artist.

Change is difficult, but it is also the essence of pre-production. The less resistant you are to change and new ideas regarding your work, the more fruitful the creative process becomes.

And…

In spite of their misgivings, I managed to convince the band at the beginning of this article that they needed to budget a few days in their schedule for pre-production. They agreed to try it for two days. They were so surprised by how much better their songs became that, at the end of the second day, they insisted on three more days.

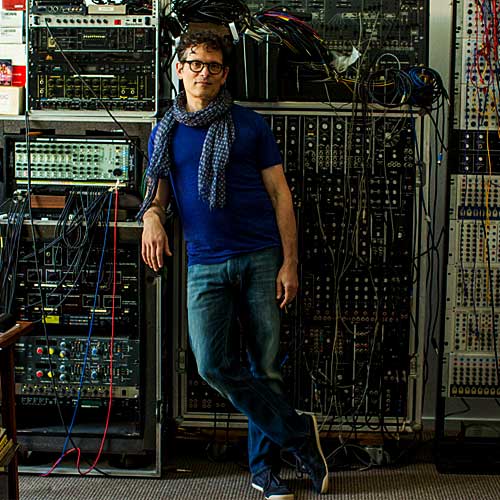

By Michel Beinhorn

Page: 1 2

|

|

|

Bloc Party |

LATEST GALLERY IMAGES

Where Israel Goes, Misery Follows

The Kanneh-Masons |

|

|