Rounder: 40 Great Years Of Music

The Rounder Records Story: The 1970s By Geoffrey Himes

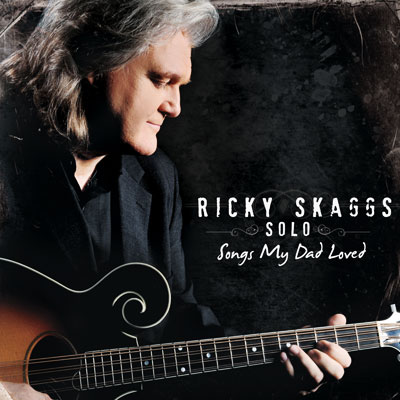

There are hundreds of thousands of records, each with its own catalogue number, but just a handful are known by those digits. Only a few albums become so freighted with meaning for a particular musical community that even the numbers on their spines are committed to memory. Mention the phrase “Rounder 0044″ to any true bluegrass fan, however, and they’ll know exactly what you mean. The official title was J.D. Crowe & the New South but to distinguish the recording from the band fans began to refer to the album as Rounder 0044. It wasn’t the first newgrass record, but it was the first to seize the imagination of the bluegrass world at large, thanks to the established credibility of Crowe and to the irresistible virtuosity of his new sidemen: mandolinist/fiddler Ricky Skaggs, guitarist Tony Rice, and Dobroist Jerry Douglas. The latter three names didn’t mean much in 1975, when the album was released, but over the next 35 years they would become indelible presences in the string-band world-and at Rounder Records.

Irwin and Leighton had approached Crowe at the Gettysburg Festival about making a banjo instrumental album. This gambit had worked for Rounder in the past, because such an album showcased a different side of an artist, emphasized the non-vocal elements that the label found so important and didn’t interfere with an artist’s more mainstream band projects. Early in Rounder’s history, for instance, the trio hoped to record their beloved Lilly Brothers, the band that played the Hillbilly Ranch in Boston seven nights a week, but a family tragedy led to

Everett Lilly moving home to West Virginia. Instead the Rounders produced an early album of the band’s banjo player Don Stover, for the 1972 album, Things in Life.. “When we started out,” Irwin explains, “my only goal was that when someone made their list of top ten banjo records or top ten fiddle records, we’d have a record that would be on that list. Don’s record was the first that met that standard.” But Crowe had something more ambitious than a banjo album in mind; he saw this upstart little label as his chance to hatch the new sound in his head.

Crowe had worked with bluegrass giants Jimmy Martin and Red Allen, but he felt restricted by the genre’s repertoire and arrangements. He wanted to include tunes from folk-music writers like Gordon Lightfoot, Nashville writers like Rodney Crowell, and rock ‘n’ roll writers like Fats Domino. He wanted to liberate his soloists from few and simple chord changes and allow them to find new progressions and new voicings. All three of those writers were on Rounder 0044, and the soloists did find those new pathways. But Crowe introduced these innovations so cunningly that the connection to bluegrass’s past was never broken. On the lead-off track, “Old Home Place,” penned by the bluegrass writers Dean Webb and Mitch Jayne, one could hear the sentiments of the past happily co-existing with the picking of the future. The album was a huge bluegrass hit and helped make Rounder a major player in that world for decades to come.

The company had prepared itself for this breakthrough by documenting the innovative edge of bluegrass. Irwin and Marian Leighton lived in Ithaca, New York, between 1967 and ‘71, where their string-band passion and community-organizing impulses led to a non-profit concert group called the Ithaca Area Friends of Bluegrass and Old-Time Music. Through that organization the couple befriended the sextet Country Cooking, which included such future newgrass stars as guitarist Russ Barenberg, fiddler Kenny Kosek, and the two banjoists Tony Trischka and Pete Wernick. The Rounder folks arranged to record the band “in a quiet room in the student union building at Cornell University,” and the uptempo “Armadillo Breakdown” demonstrates the locomotive momentum and improvisatory freedom that would later surface in groups such as Wernick’s Hot Rize, Trischka’s Skyline, and Kosek’s Breakfast Special, which also included Trischka and mandolinist Andy Statman, a later Country Cooking member When Trischka made his own banjo-instrumental album for Rounder, Bluegrass Light, he was backed by Kosek and Statman. On “The Only Way,” one can hear that they were already playing jazz solos on string-band instruments in 1973.

Down the road in upstate New York, Woodstock’s Artie Traum read an article in Sing Out about a new record company called Rounder and approached the founders, saying, “There’s a whole music community up here, and I’d like to do an album on them.” “Artie pulled that group together for this project and called it Mud Acres/ Music Among Friends,” Bill Nowlin remembers. “It wasn’t really a band, just a bunch of people who played on each other’s tracks.” Those people included Artie, his brother Happy, the Lovin’ Spoonful’s John Sebastian, the Eagles’ Bernie Leadon, the Greenbriar Boys’ John Herald, Maria Muldaur, Pat Alger, Eric Andersen, Jim Rooney, Bill Keith, Rory Block, and Larry Campbell. They did three albums for Rounder, but their most enduring song was “Killing the Blues, written and sung by Roly Salley. Thanks to the surprising intervals of its melody and the paradoxically world-weary optimism of its lyrics, it was recorded again and again, by John Prine, Chris Smither, Shawn Colvin, and most notably by Robert Plant & Alison Krauss for Rounder. These northern string bands lent a liberating innocence to the music they had learned from the Southern originators, much as the Beatles had lent a similar innocence to the American R&B they drew upon. Joe Val and the New England Bluegrass Boys, for example, had been inspired to take up the music when the Lilly Brothers moved to Boston from West Virginia. Val may have been Italian-American, but he nails “Sparkling Brown Eyes,” written by Clark Kessinger’s Kanawha label mate Billy Cox.

Also recorded in upstate New York was the Highwoods Stringband, which was spirited old-timey, with a counter-cultural look. The song “Who Broke the Lock?” always seems on the verge of flying apart even as it drives ever forward. “They had that wild, unrestrained sound that appealed to us,” Nowlin notes. “They reminded me of the Holy Modal Rounders in that way. We never had that problem where we turned up our noses if musicians weren’t ‘true folk.’” Rounder did several projects with the extended Holy Modal Rounders family, most notably Have Moicy! credited to Michael Hurley, the Unholy Modal Rounders, and Jeffrey Frederick & The Clamtones. That disc, represented here by “Sweet Lucy,” was called “the greatest folk album of the rock era” by The Village Voice’s Robert Christgau, though it was actually the greatest country-rock album of the hippie-folk genre.

Rounder’s first album to break into five-figure sales was 1972’s Back Home in Sulphur Springs, by Norman Blake, a Doc Watson acolyte and major stylist in his own right. Accompanied only by dobroist Tut Taylor on “Down Home Summertime Blues,” the tension between Blake’s laid-back tenor and his dazzling flat-picking illustrates his ability to straddle old-grass and new. Three years later J.D. Crowe & the New South became Rounder’s first album to hit six figures in sales, and the label’s central role in bluegrass’s new wave was cemented. When Skaggs and Douglas formed a new band called Boone Creek, they released the band’s eponymous debut disc on Rounder. “Memory of Your Smile” is one of Skaggs’ earliest lead vocals, and the arrangement with piano, drums and electric bass anticipates his country hits to come. When Douglas wanted to record a dobro-instrumental album, backed by Skaggs, Rice, bassist Todd Phillips, and fiddler Darol Anger, he released Fluxology on Rounder. When mandolinist David Grisman made a newgrass album with Rice, Douglas, Phillips, and two Bill Monroe alumni (fiddler Vassar Clements and banjoist Bill Keith), he called it The David Grisman Rounder Album. Skaggs sang a guest vocal on the old song, “I Ain’t Broke but I’m Badly Bent.”

In 1973 Irwin got a call from his friend Bill Smith in Nashville, who said, “We have this incredible 13-year-old fiddle player staying at our house and you have to hear him.” The kid was Mark O’Connor, and Rounder quickly put him in the studio with Blake and Taylor to make O’Connor’s debut album, National Junior Fiddling Champion. The track here, “Tom and Jerry,” featuring mandolinist Sam Bush, appeared on O’Connor’s second Rounder album, Pickin’ in the Wind, in 1976, which was followed by his third, Markology, in 1978. In 1979, he graduated from high school and joined the David Grisman Quintet. “We had good luck discovering musicians when they were young,” Irwin remembers. “We signed Jerry Douglas when he was 17, Béla Fleck when he was 16, Alison Krauss when she was 14, and Mark when he was 13.”

For all this emphasis on the innovative side of string-band music, the Rounder founders recognized that such developments didn’t mean much if they lost their ties to the music’s past. To remind musicians and listeners alike of this, the label continued to search out neglected old-timers and shine a light on them. One of their first two releases was the album George Pegram by the North Carolina banjo picker and sawmill worker. To hear him snorting and hollering about “Johnson’s Old Gray Mule” over dizzyingly fast banjo and fiddle was to realize that the distance between the most traditional Southerners and the most bohemian Northerners was not so great after all. The Rounder founders had a special weakness for the close-interval “brother duets” that ranged from the Blue Sky Boys and Delmore Brothers to the Lilly Brothers and Whitstein Brothers. A strong link in that chain was the Bailey Brothers, former stars of radio shows such as The Grand Ole Opry and Jamboree USA, who recorded “Take Me Back to Happy Valley” for the label.

When folklorist Mark Wilson discovered rare home recordings of Ed Haley, a West Virginia fiddler so influential that John Hartford later wrote an unpublished book about him, Rounder gladly put them out, including the giddy “Cherry River Rag.” When Wilson recorded one of Haley’s top disciples, Buddy Thomas, playing the similarly giddy “Kitty Puss,” Rounder released that too. And when Wilson became enthused about Cape Breton folk music, an idiosyncratic Scottish-Canadian variant on string-band music in Nova Scotia, Rounder released a bunch of those sessions, including Joe Cormier’s medley of spirited fiddle tunes, “Mrs. Scott Skinner/The Smith’s a Gallant Fireman/The Earl of Seafield’s Real.” Wilson had befriended Nowlin when they were both Boston-area grad students, and they had made several field trips together down South and to Cape Breton. Because Nowlin, Leighton, and Irwin were used to working collectively, it was easy for them to incorporate another perspective.

Ralph Rinzler, one of the Greenbriar Boys who had first inspired Nowlin and Irwin, had gone on to manage Bill Monroe, to book the Newport Folk Festival, and to record the then-unknown Doc Watson. Having booked the Cajun band, Les Balfa Freres, for Newport, Rinzler recorded them in Harry Balfa’s living room in Mamou, Louisiana, in 1965. Ten years later, after Irwin had recorded D.L. Menard in his kitchen in Erath, Rinzler trusted the new Rounder label enough to give them the Balfa tapes, including the Cajun standard, “Parlez-Nous a Boire”

(”Let’s Talk About Drinking (Not Marriage).” If the Balfas represented the more traditional roots of Cajun music, Menard, dubbed “The Cajun Hank Williams,” represented the later fusion of Cajun and honky tonk, especially on his signature cheating song, “La Porte dans Arriere” (”The Back Door”). Rinzler also founded the annual Smithsonian Folklife Festival, which took over the Mall in Washington every summer, and the Rounder founders were regular attendees.

As good 1970s leftists, they had long been frustrated that they had found so few female artists in the string-band world. At the Folklife Fest and the Delaware Bluegrass Festival, however, they found three women who were among the genre’s most important artists of either gender. Ola Belle Reed had been raised in North Carolina’s New River Valley, but like so many of their neighbors, her family had moved to the mid-Atlantic area during the Depression to find work. Those families had brought their fiddles and banjos with them, and Ola Belle, her brother Alex Campbell, and her husband Bud Reed founded the New River Ranch in Rising Sun, Maryland, to entertain the transplants. Johnny Cash, Bill Monroe, and the Louvin Brothers performed on that creekside plywood stage, but Ola Belle soon became a major attraction by dint of her songwriting and singing. Her best known composition, “High on a Mountain,” was eventually recorded by Del McCoury, Hot Rize, Marty

Stuart, Lucy Kaplansky, and many more, but no one ever sang it with the high-pitched twang and intense personal investment that Ola Belle brought to it. When Levon Helm’s daughter Amy co-founded a new folk band in 2001, she and her pals named it Ollabelle {cq} in honor of Reed.

Hazel Dickens was part of that same mid-century migration from Appalachia to Maryland, though she came from the coal fields of West Virginia and ended up in urban Baltimore. It was there she met Bill Monroe and such bohemian bluegrass lovers as Mike Seeger and Alice Gerrard. “Mike was the first person outside our culture to validate our music,” Dickens confirms. “He looked on it as an art form, while to us it was just what we did. We never thought anyone else would be interested.” It was also in Baltimore that Dickens found her songwriting gift and her singing voice. When Gerrard added her high tenor to Dickens’ lead, they created an unprecedented female equivalent of the “brother duets” so beloved by the Rounder founders. And when Dickens wrote songs as pointed as “Don’t Put Her Down, You Helped Put Her There” or “Black Lung,” her new college-educated audience heard them as political commentary. Dickens heard them as diary-like commentary on her daily life.

This disc presents just a small fraction of the records released during Rounder’s first decade, but it accurately reflects the emphasis on string-band music. A lot of it was bluegrass, newgrass, or old-time music, but even the music from far outside Appalachia was played on acoustic string instruments. Joe Cormier’s Cape Breton reels, the Balfa Brothers’ Cajun two-steps and Michael Hurley’s country-rock all featured the fiddle prominently. Even the tune “Jula Jekere” by Gambia’s Alhaji Bai Konte was string-band music of a sort. Konte played the

West African kora, which featured twenty-some strings rising vertically from a large gourd, but in the context of this box set, it’s easy to hear the kora’s echoes in the high-pitched runs of a mandolin or the low-pitched snap of a banjo.

Thus the shock of hearing George Thorogood’s “Who Do You Love?” at the end of this disc is not unlike first hearing a Rounder album in 1978 with such in-your-face drums and amps. It wasn’t the label’s first release with electric instruments (the Bob Riedy Blues Band had released Lake Michigan Ain’t No River, Chicago Ain’t No Hilly Town the year before), but it was the first widely-heard example. And soon it became more widely heard than anything Rounder had ever done. “Who Do You Love?” had been written and recorded by Bo Diddley for Chess Records in 1956, but when Thorogood did it, everything sounded quicker and thicker. Part of it was an improvement in recording studios, but part of it was also Thorogood’s guitar technique. “I try to play the whole guitar at once,” he explained. “That’s the trick: to get a big, full sound without relying on the volume knob. I’m really heavy-handed on the low strings, and if you muffle the strings with the side of your right hand so the notes don’t keep ringing, you get that chunky sound.”

Thorogood had transformed Diddley’s guitar sound, in much the same way that Diddley had transformed Muddy Waters’ and that Waters had transformed Charley Patton’s. It was still roots music, but with each adaptation, the beat got chunkier and the vocals more assertive. It was a new way to play an old tradition, not so different from what J.D. Crowe had done with Bill Monroe.

|

|

David Ford |

LATEST GALLERY IMAGES

Israel's Secret?

The Faces of Gaza |

|

|