Rounder: 40 Great Years Of Music

The Rounder Records Story: An Introduction By Geoffrey Himes

In the summer of 1962, some long-forgotten functionary at Tufts University paired two incoming freshmen as roommates with unforeseen consequences. The two teenagers, Ken Irwin and Bill Nowlin, didn’t know each other, but the quickly bonded over a shared enthusiasm for folk music. Ken had brought his Pete Seeger and Miriam Makeba albums and Bill his Kingston Trio records. They had one of the dorm’s few record players, and sometimes when they felt ornery, they’d play the high-pitched, twangy bluegrass of the Greenbriar Boys’ debut album to annoy people.

But as they did it again and again, a surprising thing happened: they began to really like the record. And when the quad was full of people they didn’t like, they’d play the high-pitched, twangy bluegrass of the Greenbriar Boys’ debut album.It dawned on them that the high harmonies and tough syncopation were not so different from the doo-wop and early rock’n'roll 45s they had loved in high school. The songs were obviously drawn from the same well of hand-me-down Southern music that the folk-revival singers were dipping into, but these versions were completely different: The rhythms were more muscular; the picking was more accomplished, and the singing was more confrontational. Before long the two students found themselves on the side of a highway, knapsacks on their backs, thumbs stretched outward, heading south in search of their first fiddle contest.

It was a conversion experience that affected not just the two college students and not just Marian Leighton, who was won over to the cause in 1967. It affected the shape of American roots music from 1970 onward, for those three friends founded Rounder Records that year and have run it ever since. Though the label soon branched out from bluegrass to embrace artists as diverse as George Thorogood, Gatemouth Brown, Irma Thomas, Keith Whitley, and Robert Plant, Irwin, Nowlin, and Leighton never abandoned that original vision. They were always interested in folk music, because they loved those songs about work and strikes, marriage and divorce, humor and violence, that arose from people performing for their friends and family. But they wanted to hear those songs delivered with more of a vigorous beat and an edgy attitude.

These three co-founders weren’t much interested in the private, polite introspection of strum-along singer-songwriters; they wanted to hear the public soul-baring that takes place in dancehalls and union halls, in barrooms and cemeteries. It didn’t matter if the musicians were working-class or middle-class, black or white, young or old, famous or obscure; it didn’t matter if they played bluegrass or blues, Cajun or Klezmer, rock or soul. What mattered was that the music remember the past and yet be as urgent as a heart attack. One can hear both those qualities on the 88 tracks spread out over the four CDs in this box set, The Rounder Records Story, whether the recording is as old as 1970’s “Johnson’s Old Gray Mare” by George Pegram or as new as 2010’s “Man with the Blues” by Willie Nelson.

When Irwin was hitch-hiking home from the Old Fiddler’s Convention in Galax, Virginia, in August, 1969, his first ride was with James Lindsey, the leader of the Mountain Ramblers on Alan Lomax’s legendary set, Songs of the South, and a frequent winner at Galax The second ride was with Ken Davidson and his wife Sherri, who offered to put up Irwin overnight at their home in Charleston, West Virginia. The young amateur folklorist, who had rediscovered and recorded Clark Kessinger and Billy Cox, offered to introduce Irwin to the old-time fiddlers who had made so many legendary records in the 1920s..Irwin eagerly delayed his return home for a day, astonished to learn that people with more enthusiasm than money, more taste than contacts, could start a record company and work with artists like Kessinger. When Irwin got back to Somerville, Massachusetts, he excitedly told Nowlin: “This guy started a record company, and he doesn’t know anything about album covers or liner notes. We know designers and writers. Why don’t we start a record company?” Nowlin’s eyes lit up, and he said, “Yeah, why not?”

The following February, Irwin and Leighton, a couple since 1967, were hitch-hiking to Mardi Gras in New Orleans when they made a detour through Florida where the Davidsons were now living. Ken Davidson pulled out a friend’s recording of banjoist George Pegram, who was such a star at the Old Time Fiddlers Convention in Union Grove, North Carolina, that he was called the Baron of Union Grove. The three bought the rights to the tape for $125. When the couple returned with Nowlin to Union Grove for the Easter weekend festival, the band category was won by the Spark Gap Wonder Boys, a group of Boston-area students who had translated their enthusiasm for old-time country music into an energetic live act. The wannabe record-company owners were sure some bigger label would snap up the band, but when none did, they offered to record the Spark Gappers.

So the fledgling record label had its first two acts, but now it needed a name. The three friends, threw out 30 or 40 names at each other - “Doorknob Records? Radiator Records?” - and just as quickly dismissed them. They weren’t getting anywhere until someone said, “How about Rounder Records?” No one could dismiss that so quickly, because it worked so many ways. One of the trio’s favorite acts was the Holy Modal Rounders, who took a wacky, bohemian approach to roots music. Rounders was the British game that gave birth to American baseball, a perfect example of evolution within a tradition. More than a few folk songs referred to rootless, footloose outcasts as rounders. And records, of course, were round. So Rounder it was. Many years later, when the Grateful Dead started a label called Round Records, copyright lawyers urged Rounder to sue. “Why should we sue,” Nowlin responded, “if they want to assume the inferior position? They’re Round; we’re Rounder. Now, if they’d called themselves Roundest,” he added with a chuckle, “we might have had a problem.”

The first two albums from Rounder Records, George Pegram and the Spark Gap Wonder Boys’ Cluck Old Hen, were released on October 22, 1970. One act was a banjo-playing sawmill worker from the North Carolina mountains; the other was a band of baby-boomer college kids who loved old-time mountain music no less than Pegram. So from the very beginning the company was combining the old and the new. When music writer Pete Welding later described the fledgling label as a home for “roots music and its contemporary offshoots,” that sounded right to the Rounder founders.

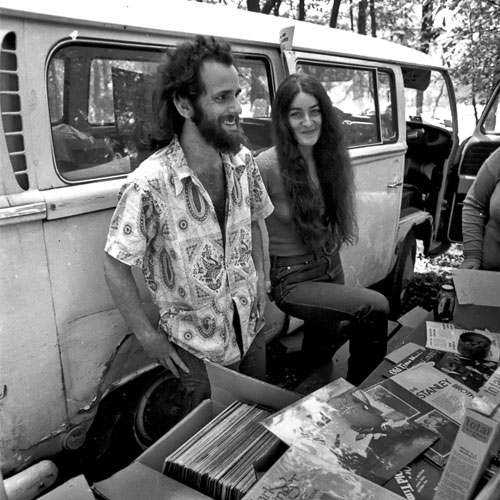

Irwin, Leighton, and Nowlin had a real record company now. They could take their cardboard boxes of 12-inch vinyl albums to the festivals down South and set up a stand to sell their wares. It wasn’t long before musicians and folklorists came up to the table, not to buy LPs but to pitch possible recordings. After a year of looking for projects to record, the trio was being asked to choose between more options than the company could handle. How would they choose among them?

The folk-music labels that they most admired were the creations of single-minded individuals: Moe Asch’s Folkways Records, Dave Freeman’s County Records, and Chris Strachwitz’s Arhoolie Records. By contrast, Rounder was being run by a Cerberus-like three-headed owner. This was a handicap, in that it made each decision potentially more arduous, though most decisions were made with surprising ease, and in the long run it proved an asset. Though their tastes overlapped to a great extent, they were passionate about different things, and one person’s passion would push a project forward while three mild approvals wouldn’t. This inevitably broadened the label into a broadly eclectic roots-music roster. Originally they all shared all the jobs , but it turned out they each had different strengths. Nowlin got interested in business negotiations and took over that side of things. Irwin really loved the recording studio and concentrated on A&R and production. Leighton loved writing and conversation so she dealt with the press and radio. But every release still needed three yeses to go forward.

Just as important, the three were able to provide emotional as well as logistical support to one another when things got tough, as they often do in the music business. There was never a burden one person had to share alone. Even when Irwin and Leighton made the difficult transition from lovers to friends, their love for the music allowed them to continue to live in the same apartment and to work for the same company. And because they always made decisions as a collective, they were quite comfortable allowing other people into the process. So when Harvard grad student Mark Wilson turned them on to some Cape Breton and Appalachian musicians, the Rounder founders were willing to trust him. When musician Artie Traum offered to record the Woodstock music scene under the name Mud Acres, the founders gave him the go-ahead. When musician Dewey Balfa suggested Cajun musicians the label should record and folklorist Mark Pevar suggested African musicians, that was fine too. Irwin, Leighton, and Nowlin were politically progressive products of the ‘60s, and they saw Rounder Records as a form of community organizing, of bringing all these people involved in roots music under a common roof where they could reach more people.

The Rounder founders didn’t pay themselves anything for the first four years as they continued to pursue their academic ambitions. But once they released landmark albums by the likes of guitarist Norman Blake and bluegrasser J.D. Crowe, they came to realize that this was no longer a hobby but a career. Then they befriended a trio of blues-rock musicians from Delaware and everything changed for good. George Thorogood & the Destroyers drew their repertoire from Robert Johnson and Elmore James, from Carl Perkins and Hank Williams, but they played the songs hard and fast. In the liner notes for the trio’s third album, Irwin, Leighton, and Nowlin recalled their initial doubts: “What to do with it? Clearly the early Rolling Stones didn’t belong on Rounder Records, largely a traditionally-based folk, bluegrass and blues label. And George Thorogood is probably closer in style and approach to the early Stones than he is to most of our catalogue.”

That didn’t stop the Rounder founders from allowing the band to sleep on their floor when the Destroyers came to Massachusetts. Nor did it stop Irwin, Leighton, and Nowlin from loving the band’s live shows. Nor did it stop them from admiring musicians who would arrange touring around their baseball team’s schedule. Finally the Rounder triumvirate decided to stop being so precious about it. Wasn’t this roots music played with skill and conviction? Hadn’t they fallen in love with the Greenbriar Boys because it was edgier and more muscular than the folk-revival singers? Wasn’t this the same thing at a different degree of edginess and muscularity?

Rounder released George Thorogood and the Destroyers in 1977. Things started slowly at first, but then all hell broke loose. Radio and the press clamored for records and interviews. Record stores were ordering dozens of copies at a time instead of two or three. The Rounder staff expanded to meet the onslaught and even then everyone worked at a frenzied pace. After three albums Thorogood had outgrown the situation; the turning point came when the trio opened for the Rolling Stones at the New Orleans Superdome and the local distributor ordered only 25 copies of the group’s three albums. A joint venture was formed with EMI America Records to take the band to the next level..

When the smoke cleared, Rounder was a changed company. It would no longer limit itself to acoustic music; it would be more open to drums, horns, and amplifiers. That opened the door to Texas blues bands, New Orleans R&B groups, Louisiana zydeco bands, Jamaican reggae groups, borderland conjuntos, Rhode Island jump-blues horn bands, and Canadian rock ‘n’ roll stars. This allowed the label to present the full range of roots music and to connect with the typical roots-music fan, who was rarely a one-genre fanatic but more typically liked blues and bluegrass, Cajun/zydeco and Tex-Mex. It worked because Irwin, Leighton (who eventually became Marian Levy), and Nowlin were those fans themselves. They loved all kinds of roots music; they just wanted to hear it with a physical push and a nothing-held-back commitment. The hundreds of thousands of listeners who bought one or more Rounder albums felt the same way.

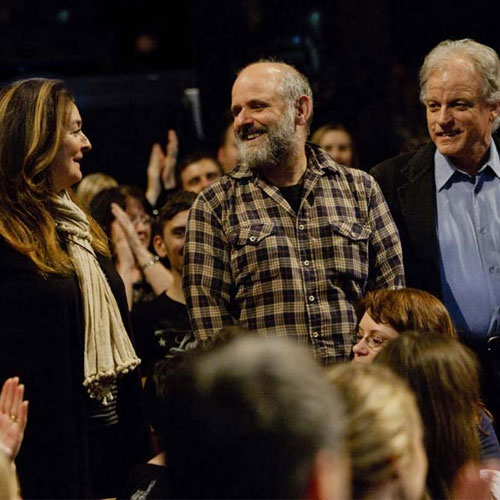

Rounder had survived the test of fire that any hit presents to a small record company and would be better prepared the next time one came along. And the next time came along with strong-selling records from Gatemouth Brown, Nanci Griffith, Beau Jocque, Madeleine Peyroux, Dailey & Vincent, and especially Alison Krauss. Rounder didn’t have to turn Krauss over to anybody, because it had better learned how to transmit roots music to a wider audience. Their promotion, publicity, and marketing had all improved to the point that Alison didn’t need to “graduate” to a major label. It had proven it knew how to get TV appearances and Grammys for its artists. It survived because the three founders and their collaborators not only had good taste but also - from the start - the pragmatism to make sure they had enough money on hand to write checks for next week’s payroll and next week’s studio session. During its 40 years of existence, the Rounder founders have seen dozens of roots-music labels start up and die out, for a number of reasons - including some good luck. Irwin, Levy, and Nowlin had both vision and that pragmatism-perhaps exemplified as well in 1997 when, in a generational move of sorts they turned over most business matters to John Virant, who had come on board as an unpaid intern and yet had worked his way up to company president/CEO. That’s why they could create so many memorable records, enjoy so many successes, and win so many awards for four full decades. When they did decide to finally sell Rounder to Concord Records in 2010, it was on their own terms and with the assurance that they would continue to shepherd the company in the near future. There has never been another record company quite like it.

Geoffrey Himes writes about music for the Washington Post, the Baltimore City Paper, Jazz Times, the Fretboard Journal and many more. His book, In-laws and Outlaws: How Emmylou Harris, Rosanne Cash, Rodney Crowell, Ricky Skaggs and Steve Earle Fashioned a New King of Country Music, will be published by the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2011. He would like to point out that some of his favorite Rounder artists - Steve Riley, Ray Wylie Hubbard, Si Kahn, Solomon Burke, Steve Jordan, Juliana Hatfield, Joe Ely, the Holmes Brothers, Joe Grushecky, Sun Ra, the Nashville Bluegrass Band, Cathy Fink & Marcy Marxer and the Tarbox Ramblers-have been squeezed out of this crowded box set.

|

|

The Low Anthem |

LATEST GALLERY IMAGES

Israel's Secret?

The Faces of Gaza |

|

|